Fall in love with the problem, not the solution. It's one of the most repeated mantras in product management, and for good reason. Too many products fail because teams jumped straight to building without truly understanding what they were solving for.

The wisdom behind this isn't new—in fact, it's ancient. Lao Tzu wrote, "You can mould clay into a vessel; yet, it is its emptiness that makes it useful." The essence isn't the solution (the vessel), but the need it serves (the emptiness). This fundamental insight has echoed through centuries of human craft and creation.

In the modern era, this philosophy found new expression through design and innovation thinking. The Stanford d.school embedded it in their design thinking methodology. IDEO championed it as core to human-centred design. Lean Startup practitioners embraced it as an antidote to solution-first thinking. The phrase itself—"fall in love with the problem"—has been attributed to various innovation leaders, but its message is universal: understand deeply before you build.

And it works. This problem-first mindset has saved countless teams from building beautiful solutions that nobody wants. It's pushed us to spend time with users, to question our assumptions, to validate before we invest. The entire Jobs to be Done framework emerged from this thinking—focusing on the underlying problem the customer is trying to solve rather than the features they say they want.

But here's the problem: not everything is a problem.

When we frame our work exclusively through the lens of "problems to solve," we artificially constrain our thinking. We miss chances to delight. We overlook opportunities to create new value. We get stuck fixing what's broken instead of imagining what's possible.

Teresa Torres opened my eyes to the power of reframing from Problems to Opportunities, and this reframe unlocked the crucial execution step of the Decision Stack mental model. This isn't just semantic gymnastics—it's a fundamental shift in how we connect strategy to execution.

Where Opportunities Sit in the Decision Stack

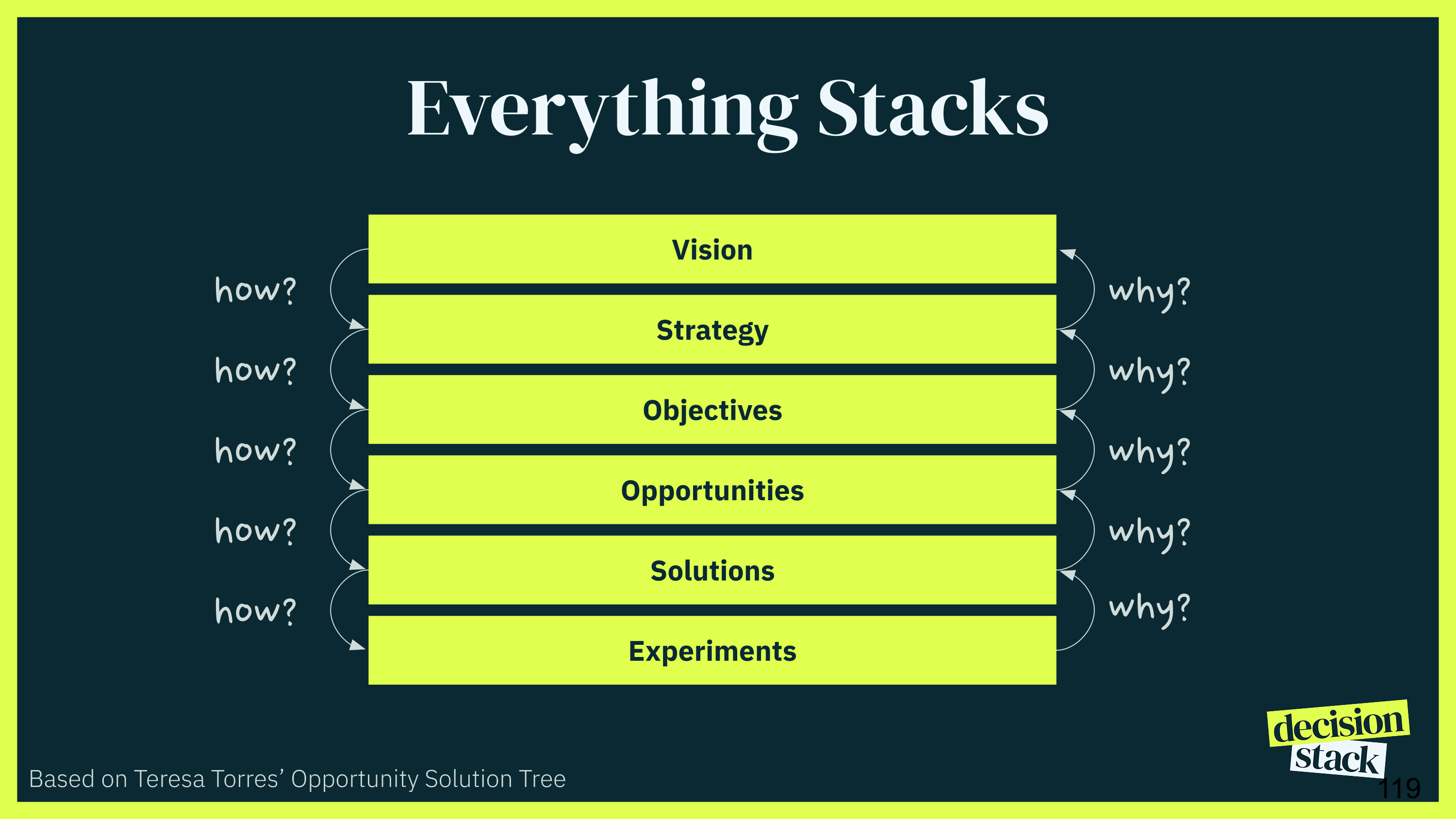

The Decision Stack is a model for decision-making that creates clear connections between different levels of thinking—from high-level vision down to execution. At its core, it's about creating alignment and traceability in our product decisions.

Opportunities form the critical bridge between Objectives (what we want to achieve) and execution (what we'll build). They represent the space where strategic intent meets tactical possibility. When we identify an Opportunity, we're essentially saying: "Here's a way we might be able to drive our Objectives forward."

This positioning matters. By sitting between Objectives and Solutions, Opportunities force us to maintain that connection between the "why" and the "what."

The Linguistic Trap of "Problems"

Language shapes thinking. When we talk exclusively about "problems," we prime ourselves for a particular mindset:

- Problems imply something is broken and needs fixing

- Problems suggest a negative current state that needs remediation

- Problems often lead to convergent thinking—finding THE solution to THE problem

The product management community has tried to escape this trap through various semantic acrobatics. We talk about "customer needs" or "jobs to be done." These are better, but they're still fundamentally reactive framings.

Opportunities, on the other hand, encompass all of these and more:

- An opportunity might be a problem that can be solved

- An opportunity might be a chance to delight users in unexpected ways

- An opportunity might be a way to capture new value or enter new markets

- An opportunity might be about removing friction, adding joy, or creating entirely new possibilities

This isn't just wordplay. The shift from Problems to Opportunities fundamentally changes how teams approach their work. Instead of asking "What's broken?" we ask "What's possible?"

The Power of Divergent Thinking

This reframing aligns beautifully with established frameworks for innovation and design thinking. The Design Council's Double Diamond model shows us the importance of diverging before converging—of exploring the full possibility space before narrowing to specific solutions.

When we think in terms of Opportunities rather than Problems, we naturally embrace this divergent phase. A single Objective might spawn dozens of Opportunities. Some might address existing problems, others might create entirely new value propositions. This richness is what we want in the exploratory phase of product development.

Teresa Torres' Opportunity Solution Tree makes this structure explicit. At the top, we have our desired Outcome (similar to an Objective in the Decision Stack). Below that, we map out multiple Opportunities—different ways we might achieve that outcome. And below each Opportunity, we explore multiple possible Solutions.

Teresa’s tree structure enforces something crucial: one-to-many relationships. One Outcome spawns many Opportunities. One Opportunity spawns many Solutions. This is divergent thinking made visual.

Working the Tree in Both Directions

Here's where the Opportunity framing becomes particularly powerful: it works equally well whether you're working top-down or bottom-up.

Top-Down: From Objectives to Opportunities

When you start with a clear Objective or desired Outcome, Opportunities give you permission to think broadly about how to achieve it. Let's say your Objective is to "Increase user engagement by 30%."

Instead of immediately jumping to "What problems are causing low engagement?" you ask, "What opportunities do we have to drive engagement?" This might surface:

- Opportunities to make the product more delightful to use

- Opportunities to create new reasons for users to return

- Opportunities to remove friction from key workflows

- Opportunities to add social elements that increase stickiness

- Opportunities to better align the product with user goals

Each of these opens up different solution spaces, leading to more creative and comprehensive approaches.

Bottom-Up: From Solutions to Opportunities

Equally important is the reverse journey. Teams often have feature ideas, solutions, or technical capabilities looking for a home. Instead of forcing these into a "problem" framework, we can work upward to understand the Opportunity they represent.

You have an idea for a real-time collaboration feature? Work upward: What opportunity does this represent? Perhaps it's an opportunity to "Enable users to collaborate as a team." Now you can explore: What other solutions might address this same opportunity? What Objective does this opportunity serve? Are there other opportunities that might better serve that Objective?

This bidirectional thinking prevents two common anti-patterns:

- Solution-first thinking: When teams fall in love with a solution and retrofit a problem to justify it

- Local optimisation: When teams solve the immediate problem without considering whether there are bigger opportunities to pursue

Avoiding the Anti-Patterns

The shift to Opportunity thinking helps us sidestep several persistent anti-patterns in product development:

The Hammer Looking for Nails

When we're problem-focused, we often define problems in terms of the solutions we're comfortable with. A team strong in machine learning suddenly finds ML-shaped problems everywhere. By thinking in terms of Opportunities instead, we keep the solution space open longer, allowing for more creative and appropriate solutions to emerge.

The Local Maximum Trap

Problem-solving often leads to incremental improvements—making the current thing less bad. But what if the real opportunity is to reimagine the experience entirely? Opportunity thinking gives us permission to explore adjacent possibilities and potentially discover global maxima we'd never reach through incremental problem-solving.

The Feature Factory

When teams get stuck in problem-solution mode, they often end up in a feature factory—cranking out solutions to an endless stream of problems without stepping back to ask whether they're pursuing the right opportunities. The Opportunity layer forces that strategic pause: Is this opportunity worth pursuing given our Objectives?

Putting It Into Practice

Making this shift in your team doesn't require wholesale process change. Start with these simple adjustments:

In Discovery: Instead of only cataloguing problems, create an Opportunity Bank. For every problem you identify, ask: "What opportunity does this represent?" Then ask: "What other opportunities exist in this space?"

In Planning: When reviewing your roadmap, map features back to Opportunities, not just problems. This often reveals when multiple features are actually different solutions to the same opportunity—a chance for consolidation and focus.

In Retrospectives: Don't just ask "What problems did we solve?" Ask "What opportunities did we capture? What opportunities did we miss?"

In Stakeholder Conversations: Frame discussions around opportunities to move from defensive (fixing problems) to offensive (creating value) positioning.

The Bottom Line

Problems are a subset of Opportunities, not the whole picture. By expanding our lens from problem-solving to opportunity-capturing, we create space for more innovative, strategic, and impactful product development.

This isn't about ignoring problems—they're still important opportunities to address. It's about recognising that if all we do is solve problems, we'll only ever make things less bad. To make things genuinely better, to create delight, to drive real value—we need to think in terms of opportunities.

In the Decision Stack, Opportunities are where strategy becomes tangible. They're where we translate lofty Objectives into actionable paths forward. And by framing them as opportunities rather than problems, we give ourselves and our teams permission to think bigger, explore wider, and ultimately deliver more value.

So yes, fall in love with the problem. Just remember—the problem is not everything is a problem.