Let me guess: you've implemented OKRs, but they're not delivering the transformational results you expected. You're not alone. Research shows that 60% of organisations struggle with OKR implementation. Despite the evangelism and success stories from Google, most teams implementing OKRs either restart or abandon the framework entirely. The problem isn't that OKRs don't work—it's that we're implementing them wrong.

The uncomfortable truth is that most organisations are trying to copy-paste Google's approach without understanding that OKRs aren't a rigid framework but a philosophy that must adapt to your specific context. We've confused the map for the territory, mistaking one company's implementation for universal truth. The result? Elaborate to-do lists masquerading as strategic objectives, cascading confusion instead of alignment, and teams going through the motions without achieving meaningful outcomes.

A Brief History of OKRs

OKRs didn't spring fully formed from Silicon Valley's collective consciousness. They evolved from Peter Drucker's 1954 Management by Objectives, through Andy Grove's transformation at Intel, to John Doerr's evangelism, and finally to Google's specific implementation. Each step involved adaptation and evolution based on organisational needs.

Andy Grove, Intel's legendary CEO, took Drucker's annual MBO system and made it quarterly, added specific measurable key results, and critically, decoupled it from performance reviews. His insight was simple but powerful: "Where do I want to go? How will I pace myself to see if I'm getting there?" When John Doerr learned this system at Intel in 1975 and later introduced it to Google in 1999, the 40-person startup didn't just adopt Grove's system—they adapted it. Complete transparency, 60-70% success rate targets, bottom-up goal setting—these weren't Grove's ideas, they were Google's innovations for their specific context. The lesson here isn't to copy Google's OKRs. It's to understand that OKRs evolve, and successful implementation requires matching the high-level concept to your organisation's specific reality.

Why Your OKRs Are Broken

You may not suffer from all of these, but any one is enough to derail OKRs and turn a great tool into a mess:

Shaky Strategic Foundations

1. No Clarity on Vision or Strategy

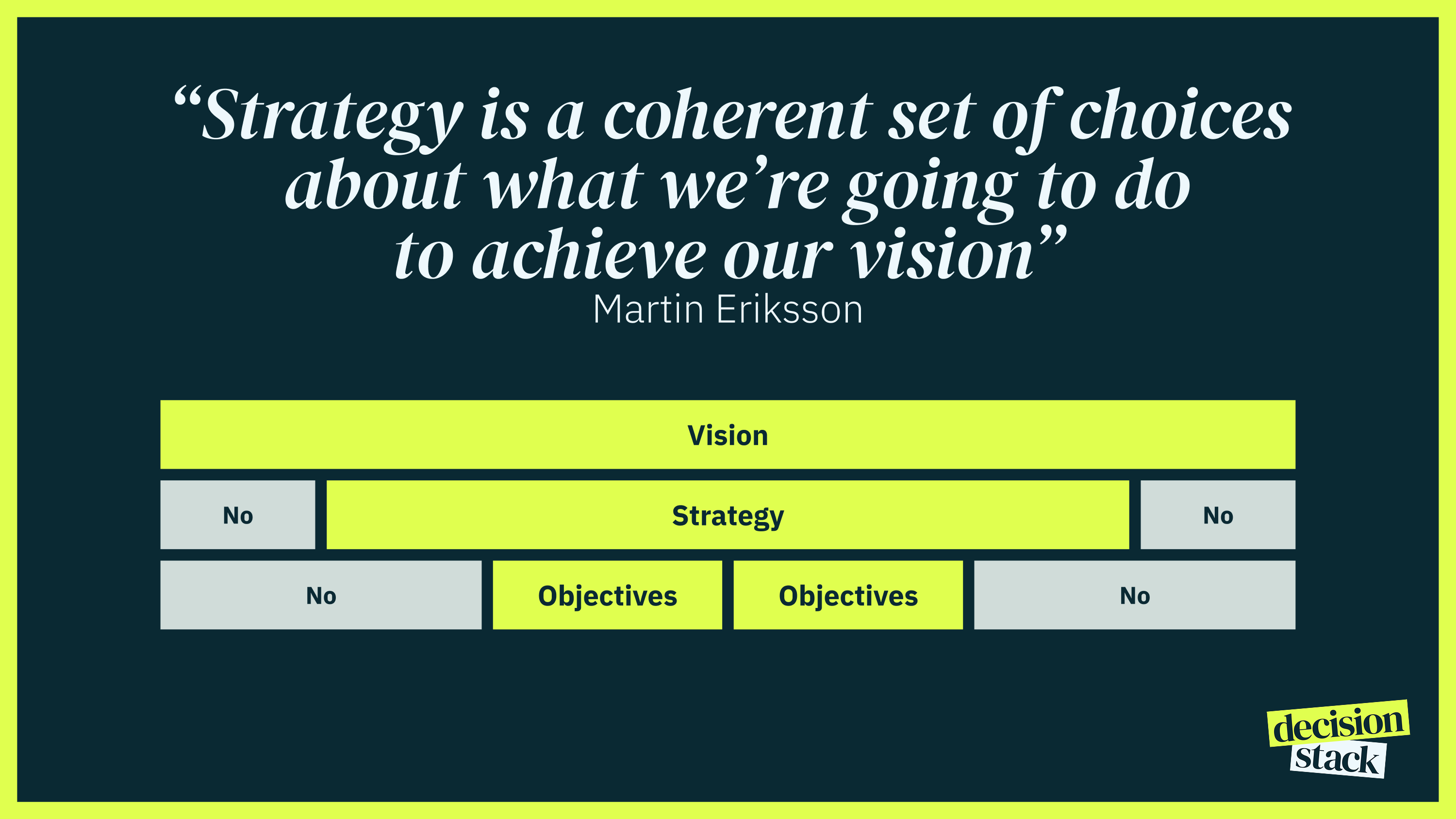

Christina Wodtke nails it in Radical Focus: "Using OKRs without a mission is like using jet fuel without a jet. It's messy, undirected, and potentially destructive." But a vision/mission isn't enough. You also need to make strategic choices—real choices that say no to good opportunities to focus on great ones.

This is where the Decision Stack becomes your connecting tissue. Your mission and vision sit at the top, your strategy makes explicit choices about how to achieve them, and only then do your OKRs make sense. Without this foundation, you're essentially asking teams to set goals in a strategic vacuum. As I've written before in "Your Strategy Probably Sucks", most strategies are just lists of things we'd like to be true, not actual choices about what we will and won't do.

The Decision Stack creates the context that makes OKR setting possible. When you've made real strategic choices—as explored in "Strategy Into Action: Finding the Courage to Make Choices"—your OKRs become obvious. They're the measurable expression of your strategic choices, not arbitrary metrics plucked from thin air.

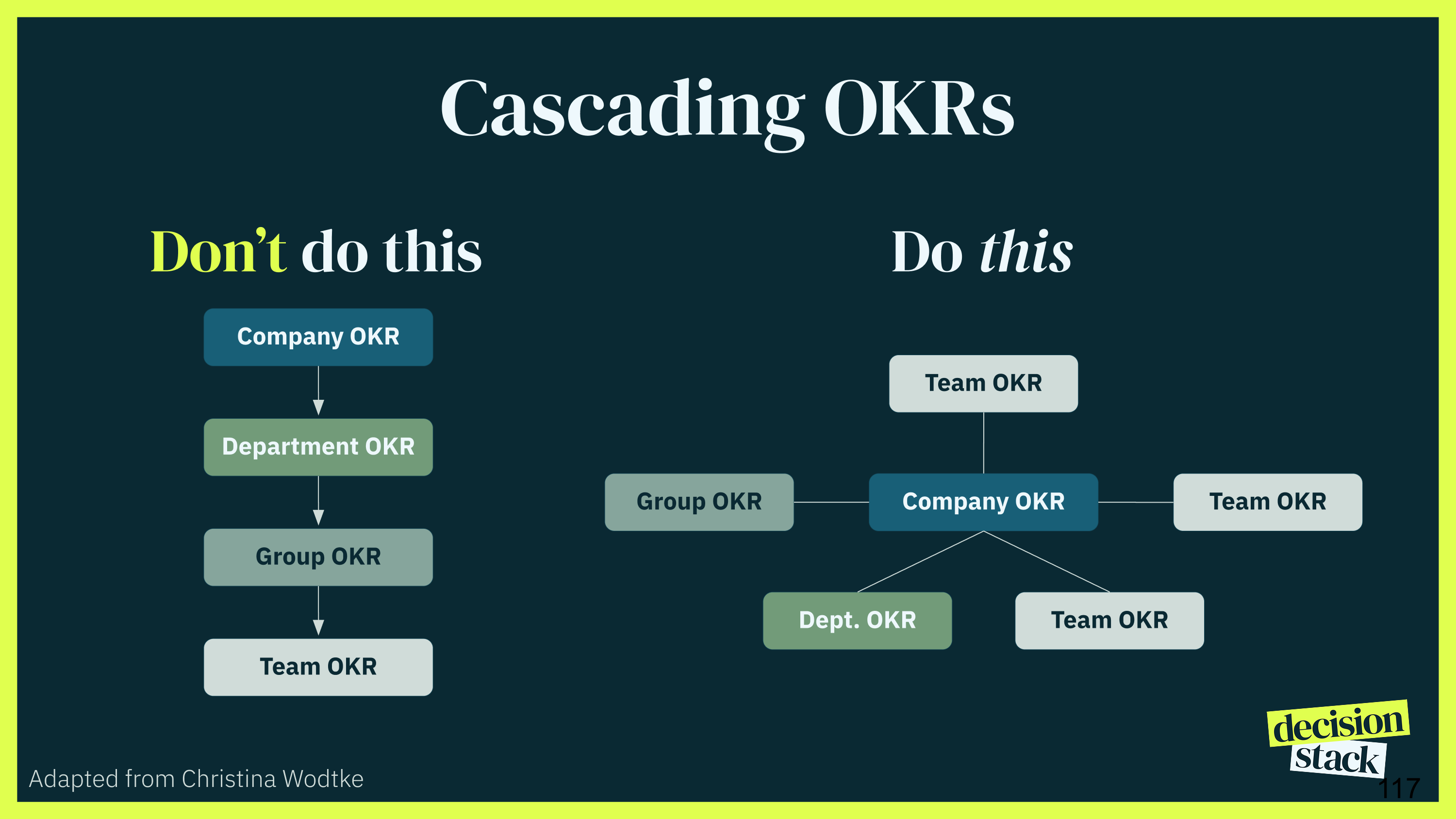

2. The Cascade Fallacy

Here's a critical insight from Christina Wodtke that most organisations miss: OKRs don't cascade. They should all be at most one step removed from the company's goal. When you create elaborate cascading hierarchies of OKRs, you're not creating alignment—you're creating a game of telephone where the original strategic intent gets lost in translation.

But here's the nuance: while OKRs shouldn't cascade, decisions do. The Decision Stack recognises that strategic decisions flow through an organisation, creating context and constraints that inform local decision-making. Your company's OKRs should directly reflect your strategy, and team OKRs should directly support company OKRs. That's it. One step removed, maximum.

3. Too Many OKRs

I've seen organisations with 10, 20, even 30 OKRs. This is madness. You can only have one top priority. If everything is important, nothing is. You should have 2-3 Objectives at most, each with 3-5 Key Results. That's it.

The proliferation of OKRs is usually a symptom of the lack of strategic choices mentioned earlier. When you haven't decided what's truly important, everything seems important. The result is a scattered organisation pulling in multiple directions, achieving nothing of significance.

Blinded to Implementation Reality

4. Choosing Comfort Over Impact

Organisations consistently pick the easiest goals rather than the most impactful ones. As Matt LeMay argues brilliantly in his book Impact First Product Teams, we need to focus relentlessly on what will actually move the needle, not what's comfortable to measure or easy to achieve.

This requires courage. The most impactful objectives are often the ones with the highest risk of failure, the ones that require cross-functional collaboration, the ones that challenge existing power structures. But these are precisely the objectives that justify the effort of implementing OKRs in the first place.

5. No One Owns the OKRs

Here's a pattern I see repeatedly: OKRs get set in a quarterly planning session, everyone nods, and then they're forgotten until the end-of-quarter review. The problem? No one actually owns them.

Ownership should sit with the team—they're responsible for the outcome, so they should be responsible for setting, tracking, and managing the goal. This isn't about assigning an "OKR manager" who nags everyone about updates. It's about the team that will deliver the results, taking true ownership of both the goal and the process. Without this ownership, OKRs become theatre—a performance we go through quarterly without real commitment or accountability.

6. Your Time Horizon May Be Off

Once you're established, OKRs generally run quarterly, but that's not gospel. I quite like running them every six weeks—it creates more frequent check-ins and faster learning cycles. The question isn't "what's the standard?" but "what's right for your context?"

It's also worth noting that it's perfectly fine to keep the same OKR over many time periods. The cadence isn't about constantly changing goals—it's about checking progress and confirming that this is still the most important goal. If you're making steady progress on the right objective, changing it just because the calendar flipped is organisational ADHD, not strategic thinking.

7. Data Maturity Comes First

Research shows that a lack of data infrastructure is a key failure mode for OKRs. You can't measure what you don't track. Yet organisations try to implement OKRs without basic metrics infrastructure, inevitably transforming them into elaborate to-do lists rather than outcome-focused goals.

Before you even think about OKRs, ask yourself: Do we have the data we need? Is it accessible? Is it timely? If you're planning to measure customer satisfaction but have no way to actually measure it, you're setting yourself up for failure. Data maturity has to come first. Build the infrastructure, establish the baselines, then set the goals.

8. Confusing Objectives with Key Results

I see this constantly: organisations mixing up their Objectives (what we want to achieve) with their Key Results (how we know if we're on the right path). An Objective should be qualitative, inspirational, and memorable. Key Results should be quantitative, measurable, and time-bound.

Most good OKR implementations I've seen have evolved to using OKRIs—explicitly separating Initiatives from Objectives and Key Results. I take this a step further and use Opportunities (OKROs?) - the next step in the Decision Stack - instead of Initiatives to emphasise a more outcome-oriented approach. This creates clarity: the Objective is what you want to achieve, Key Results are how you'll measure progress, and Opportunities are the things you'll pursue to get there. This separation prevents the common mistake of turning OKRs into task lists.

Mismatched Culture Fit

9. The Outcome Orthodoxy

Here's where I'll be controversial: sometimes an output is okay. The OKR orthodoxy insists on outcomes over outputs, but context matters. When I helped build the first version of Cazoo, we were starting from zero. We needed to build an e-commerce site. This wasn't rocket science requiring sophisticated outcome metrics—it was a foundational output that needed to exist before we could drive outcomes.

The key is knowing when outputs are appropriate (usually in early stages or for foundational work) and when you need to shift to outcomes (when you're optimising and growing). Don't let orthodoxy override common sense.

10. Mismatched Incentives

While OKRs should not be used for performance reviews or bonuses (Grove was clear on this), they can't be completely divorced from what your teams are incentivised to achieve. If your OKRs say one thing but your bonus structure rewards another, you're setting up an impossible conflict.

The solution isn't to tie compensation to OKRs but to ensure your overall incentive structure doesn't actively work against your OKRs. This requires thinking holistically about organisational design, not just goal-setting.

11. Missing Check Metrics (Turning it up to 11)

When setting Key Results, too many organisations only set growth or revenue targets without corresponding quality metrics. You want to grow users by 50%? Great. What about user satisfaction? You want to increase revenue by 30%? Wonderful. What about customer retention?

Every growth metric needs a check metric to ensure that growth doesn't come at the cost of quality or customer experience. This balance prevents the kind of growth that looks good in quarterly reviews but destroys long-term value. Harvard, Kellogg, and Wharton's Goals Gone Wild joint research paper shows that people given specific goals without guardrails were more likely to engage in unethical behaviour—your check metrics are those guardrails.

When NOT to Use OKRs

Sometimes the bravest decision is recognising that OKRs aren't right for your organisation—at least not yet. If you're in pure discovery mode, if you lack basic data infrastructure, if your culture is command-and-control, or if you're changing direction weekly, OKRs will only add confusion.

Consider alternatives like NCTs (Narrative, Commitments, Tasks), which focus on storytelling and context rather than metrics. Or simple priority lists. Or themed quarters. The point isn't to force-fit OKRs into every situation but to find the goal-setting approach that matches your organisational reality. Fix the prerequisites first—establish some stability, build data capabilities, create psychological safety—then revisit whether OKRs make sense.

Whatever tool you use - make sure you're connecting the dots from strategy to action so you can provide clarity on what's important right now on that journey.

The Path Forward

OKRs, like any tool or model (including the Decision Stack!), should never be blindly copied from another organisation. Google's implementation worked for Google. Intel's worked for Intel. Yours needs to work for you.

The principles are sound: focus on what matters, measure progress, create alignment, and inspire stretch. But the implementation must reflect your organisation's culture, maturity, context, and strategic choices. This isn't about perfecting a framework—it's about using a framework to perfect your execution.

As Christina Wodtke reminds us, "The original OKR system was just a way to set smart stretch goals. But the system around it—commitments, celebrations, check-ins—makes sure you continue to make progress towards your goals." The magic isn't in the OKRs themselves but in how they become part of your organisational rhythm.

Stop trying to implement Google's OKRs. Start building your own, grounded in your strategy, adapted to your context, and focused on what actually matters for your organisation. That's when OKRs stop being broken and start driving real results.